Days before a provincial election in Quebec, a center-right party promising to slash immigration and to kick out all immigrants who fail tests of “values” and the French language is in a dead heat with the incumbent Liberals who have governed the province for most of the past 15 years.

The Coalition Avenir Quebec, a party led by businessman Francois Legault, is tied with premier Philippe Couillard’s Liberals, with each party supported by 30 percent of decided voters, according to a poll by Ipsos for La Presse and Global News. That makes it likely the Oct. 1 election will produce a minority government.

This year’s contest will be the first in nearly six decades where the “national question” — whether French-speaking Quebec should separate from the rest of Canada — is not a campaign issue. But those bitter independence battles have morphed into acrimonious fights over immigration and perceived threats to Quebec’s francophone identity.

“Young Quebecers are less attuned to independence, so the old nationalist discourse on sovereignty is not as strong,” said Chedly Belkhodja, a professor at Concordia University’s School of Community and Public Affairs in Montreal. “The big questions now are about identity and what Quebec will look like.”

The hot-button topic of immigration emerged as a significant issue two weeks into the election campaign when Legault — then the clear front-runner — detailed his immigration platform.

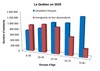

Legault plans to cut immigration by 20 percent. He has also pledged to administer French language tests and “Quebec values” tests to all immigrants within three years of arriving in the province. Those who flunk would be expelled.

“The risk is that our grandchildren won’t speak French,” Legault said. “Quebec, in North America, surrounded by hundreds of millions of Anglophones, will always be vulnerable.”

Couillard, whose Liberals plan to raise the immigration quota to 60,000 people per year, told Legault during one debate that his tests were making people “afraid” of him. Immigration, Couillard claimed, had become the “ballot question.”

Experts say that many of Legault’s fears about threats to the French language are unsupported and that ejecting immigrants from the province is unconstitutional on its face. By law, all children, including those of immigrants, attend schools where the language of instruction is French. And according to a 2017 Statistics Canada report, over 80 percent of immigrants reported being able to hold a conversation in French.

Still, Legault is making the calculation that this policy will appeal to voters outside of the province’s big cosmopolitan cities, where people might be “insecure about their identity as Quebecers,” said Linda Cardinal, a social sciences professor at the University of Ottawa.

Though Quebec’s current immigration quota is 50,000, the province selects approximately 30,000 economic migrants. Ottawa is responsible for selecting the rest, mostly,refugees or those applying for family reunification. Under a Canada-Quebec accord on immigration, the federal government provides Quebec with funding — much more than other provinces get — to support the integration of newcomers.

A report released last year from the Institut de Quebec, a public policy think tank, called for an increase in the number of immigrants admitted to the province to help address the severe labor shortages resulting from Quebec’s low birthrate and graying population.

Many municipalities and businesses have also said that they want more immigration, not less. A number of businesses have actively hired some of the “irregular” border-crossers from the United States who have been arriving in Canada on foot since 2016 to fill the shortages.

“When politicians play with these things, they have to be really careful,” Cardinal said, pointing out that the Coalition Avenir Quebec has seen its polling numbers decline as the immigration debate has intensified.

This would not be the first time that an appeal to identity politics has backfired during a provincial election campaign.

In 2014, the ruling Parti Quebecois failed to pass a “Charter of Values,” which would have banned the wearing or display of “conspicuous” religious symbols, such as turbans and hijabs, in the public service, though thousands of crosses were “grandfathered” in. It lost the election to the Liberals who opposed the charter.

But then the Liberals waded into similar territory when they passed a law banning face coverings for those receiving public services in 2017. (Legault’s party said the law didn’t go far enough).

In the spring of 2016, the Liberals announced plans to hold consultations on systemic racism in Quebec, a proposal that became more urgent in the wake of a shooting at a mosque in a town outside of Quebec City that killed six worshipers and injured dozens more earlier that year.

But after the province’s opposition parties complained and Liberal lawmakers blamed the consultation for a by-election loss in a traditional Liberal stronghold in 2017, the government scrapped the inquiry.