Peter MacKay may or may not have a French problem. In Quebecor’s newsrooms, he does: The cover of Sunday’s Journal de Québec alleged he had officially declared his candidacy for Conservative leader with the words “j’ai sera candidate” (not “je serai candidat”). It was marked wrong in red pen. The headline underneath, in English, was “Good luck, mister!”

Others disagree. Ken Whyte, founding editor of this newspaper, recently argued in The Globe and Mail that the Conservatives should stop worrying about their prospective leaders’ bilingualism, for the simple reason that “Quebec isn’t attracted to bilingual leaders from outside Quebec.”

The debate will rage on, and it will have two main thrusts.

One is: “Does it matter?” The answer is, simply, no one knows. It’s up to the voters — and almost exclusively to Quebec voters, who are charmingly unpredictable. Whyte includes Jack Layton in his contention that Quebecers are only attracted to “their own” bilingual politicians, but Layton, who had lived in Toronto for 40 years before the NDP’s 2011 breakthrough, could just as easily disprove the rule.

Two is far more complicated: “Why isn’t the person in question bilingual?”

It is surprising that someone with as much experience and longstanding ambition as MacKay wouldn’t speak better French. And if you want to be judgmental, you could say there’s no excuse: government ministers have access to the best available instruction.

Inevitably in these discussions, however, someone dares mention the unspeakable truth: that when it comes to bilingualism, not all Canadians are born equal. Conservative MP and possible leadership candidate Michelle Rempel Garner suggested bilingualism was a matter of “privilege” — “either financially, access to education, or time required.” And the National Post’s Alberta correspondent, Tyler Dawson, ventured that in most of the country, “it’s nearly impossible to finish high school fluent in French and English.”

It’s frankly bizarre that Canadians who think bilingualism is important could be this misinformed

These perfectly axiomatic observations produced the standard anecdote-laden blowback. Author and journalist Chris Turner boasted of his “fully bilingual” 14-year-old daughter, the beneficiary of “a public immersion program in Calgary, which is maybe Canada’s least French city.” Former Parliament Hill reporter Rosemary Thompson claimed “there are many options in the public school system for French” in “rural Alberta.” Shannon Phillips, the Alberta NDP’s finance critic, claimed “there is French-language education of high quality almost everywhere in this country.”

It’s frankly bizarre that Canadians who think bilingualism is important could be this misinformed. The internet is full of studies, papers and op-eds from the Official Languages Commissioner, the Senate’s Standing Committee on Official Languages and the various chapters of Canadian Parents for French bemoaning widespread lack of access to French-as-a-second-language education.

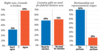

The numbers back that up. Never mind graduating high school bilingual; the vast majority of Canadian students aren’t even studying it after elementary. In the 2017-18 school year, excepting Quebec and New Brunswick, just under 50 per cent of Canadian Grade 9 students were in either core French or French immersion programs. In Grade 10 that was down to 22 per cent; in Grade 11, 15 per cent; in Grade 12, eight per cent.

Where French classes are available, moreover, they are too often shoddy. A 2017 report from the Senate committee noted a study finding 78 per cent of teachers teaching core French in British Columbia “felt uncomfortable speaking French.” Why would parents waste their kids’ time with that, if competent instruction in Mandarin, Punjabi or Japanese were available down the hall? (French isn’t mandatory at any grade level in British Columbia.)

As for French immersion, demand vastly outstrips supply. Lotteries and waiting lists are de rigueur. The Senate report told of cases where parents “camp(ed) outside schools to enrol their child in French immersion programs (for) up to four days.” Most parents have to go to work.

When it comes to bilingualism, not all Canadians are born equal

More fundamentally, though, immersion is a tool for parents who have decided very early on they want their kids to be bilingual. It is of no use to children whose parents are not so inclined, which is to say the vast majority of children. In many cases, even if those children enjoy and excel at core French, they will have few opportunities to pursue it beyond middle school.

No one is arguing they can’t become bilingual later, with considerable effort. Equally, no one would argue that’s anything but a crippling blow to the chances of that happening.

As it stands, then, the formulation “the prime minister must be bilingual” does indeed privilege a minority of Canadian children with respect to another implicit formulation: “any child can grow up to be prime minister.” That’s not a good thing. And the bilingualism requirement, while informal, is never likely to change: It is not unreasonable to expect the prime minister of a bilingual country to be bilingual. What’s unreasonable is that a bilingual country would make it so bloody difficult for a motivated K-12 student to learn his or her second language.

Parents who don’t have to worry about that would be far better off lobbying their respective education ministries on behalf of those not so lucky than wallowing in their privilege and tut-tutting at lesser unilingual mortals.

• Email: cselley@nationalpost.com | Twitter: cselley

POPULAR ON NP RIGHT NOW

Coronavirus live updates: B.C. man presumed to have coronavirus, thought to be first official case

‘A giant step toward peace’: Trump proposes Palestinian state with capital in eastern Jerusalem

Rex Murphy: The PM has changed his look. But it’s a policy change that’s needed